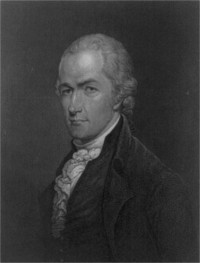

Alexander Hamilton, by William J. Weaver – US State Department, Public Domain

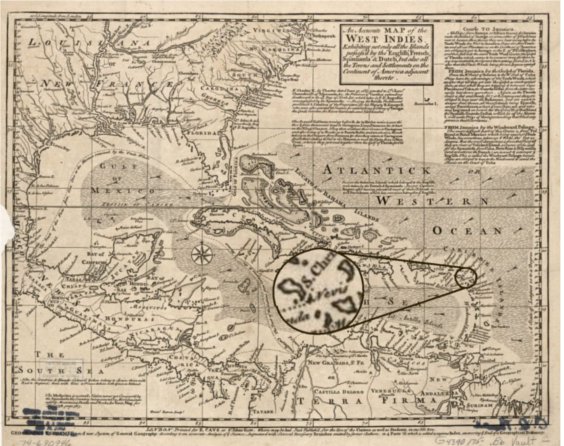

To understand the complicated life of Alexander Hamilton, understanding the culture of his time is necessary. Alexander Hamilton was born on the island Nevis, part of the British West Indies, to Rachel Faucette Lavien and James Hamilton. Drama and scandal marked the circumstances of his birth and plagued him until long after his death.

Public domain painting from the Library of Congress.

The West Indies, owned by the British at this time, were best known for their prized sugar crops. Together this small collection of islands generated more wealth for Britain than the North American colonies combined. Its distance from the main countries made it the ideal dumping ground for those not bad enough to be hanged and yet not good enough to reside with civilized people which meant that the island where Alexander spent his childhood was populated by thieves, petty criminals, slave-owners and overseers, prostitutes, merchants with shady business morals, and the like.

There was a drastic difference between upper and lower class and emphasis on good reputation and honor. This class- and status-obsessed culture made an enormous impact on Alexander. Ron Chernow, renowned historian writes, “Plantation society was a feudal order predicated on personal honor and dignity, making duels popular among those who fancied themselves noblemen.” Slavery was so prevalent, that everyone, even poor people, had numerous slaves that were either kept home for work or rented out to make a little money on the side. This is the world Alexander Hamilton grew up in.

Childhood

Young Alexander Hamilton, public domain image

A nasty divorce between Alexander’s mother and her husband Johann Lavien left her unable to legally marry again. Rachel Faucette Lavien had Alexander and his brother James out of wedlock with James Hamilton. James Hamilton was the son of Scottish Laird and status-conscious Alexander played up his noble relations whenever his illegitimacy was attacked. James left his family when Alexander and James, Jr. were 10 and 12 respectively. Rachel opened a small shop to support her family and kept a goat. She supplemented her income by renting out slaves inherited at her mother’s death.

Alexander was an avid reader growing up and especially loved poetry. His mother taught him French which made him a comfortable bilingual and extremely useful to George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

In a life already fraught with drama, the small family’s life took another unfortunate turn for the worse when Rachel and Alexander were both struck with an unidentified illness, killing Rachel less than two years after they were abandoned by James. Their house was inherited by Rachel’s only legitimate son, Peter, and the boys went to live with their cousin, Peter Lytton, son of Rachel’s sister, Ann.

Peter Lytton’s many failed business attempts drove him to commit suicide, leaving no provision for the boys. James Lytton, Peter’s father and James and Alexander’s uncle, tried to adopt the boys, but the suicide complicated things, and he died of heartbreak less than a month later.

Alexander went to live with Thomas Stevens, a well-respected merchant. Alexander Hamilton and Stevens’ son, Edward, bore such a close resemblance and had such similar mannerisms, behavior and interests, it is speculated that the two were actually brothers, and perhaps even twins, not just friends. This might explain why Edward and Alexander were such close friends their entire lives, while Alexander all but lost contact with his brother and father. It might also explain why Thomas Stevens opened his home to Alexander but not his brother James.

Teenage Years

Hamilton spent part of his teenage years working as a clerk for an import/export business, Beekman and Kruger, which dealt in every imaginable commodity. It gave an expansive knowledge of commerce, traders and smugglers and sparked his firm belief that a uniform currency would be beneficial for merchants. Slave traffic was a large portion of his business. He was responsible for inventory of all stock, which most likely included slaves to be sold to traders.

As many great people do, Hamilton knew he was born for greatness. He was determined that his life, though started in scandal and in misfortune, would lead to greatness. He read voraciously and was self-taught in almost all areas of his education, helped, no doubt, by his job.

He began writing poetry and sending it to the Royal Danish American Gazette, the island’s newspaper. He had no idea that this would be the tool to get him off the island. A missionary to the island named Henry Knox, who also moonlighted as journalist at the Gazette, befriended the young Hamilton and encouraged his writing.

When the biggest hurricane the islands had ever seen swept the island, it would be the turning point in Hamilton’s life. Alexander wrote a letter to his father describing the hurricane. Knox encouraged him to publish it in the Gazette. The letter was so well-written that a collection was taken up for the talented author to go to America to be educated. In 1772 at 16 years old, Alexander Hamilton left the island of St. Croix and never looked back. He rarely spoke of his childhood and never returned.

Collegiate to Captain

Alexander was in college in New York when the first stirrings of the Revolutionary War began. He was a quick study, worked hard, and never accepted less than his best from himself. He was intelligent, quick-witted, and sharp-tongued. He was very self-conscious about his appearance, his attire, and how others perceived him. He also had a famous attraction to women and was known for his flirtatious chivalry.

Perhaps the first impressions made on his political views were by men who were not trying to overturn the social order; they simply wanted to modify it. Hamilton embraced these views as well, causing others to accuse him of being pro-British. He was in favor of the Revolution and wanted the colonies to be free of Britain, but he feared the effects of long-term habitual disorder, showing very mature views for his age.

The first political piece he ever wrote was directly after the Boston Tea Party in 1773. He wrote a piece for the New York Journal and published it. This became a favorite way to broadcast his views and opinions. He became a sort of “child of the revolution.” He spoke at rallies, publicly supporting General George Washington‘s proposed ban on British imports and encouraging the colonies to unite.

He, like other political leaders of the time, hoped to solve the war in courtrooms and on paper, but like other 19-year-olds, he craved martial glory.

After the Battle of Lexington, volunteer militia sprung up all over the colonies and Hamilton joined one in New York. As well as his college studies, he now began his own personal military education. He read all kinds of war strategy books until he was as knowledgeable as any officer, if not more. He was still writing and sending articles to the Journal, and, on top of this, he began preliminary legal studies. He never formally graduated from college because the Revolutionary War broke out.

At the age of 21, Hamilton became a Captain of an artillery whose job was to protect New York. As in everything, he was a perfectionist and fastidious dresser, saying “smart dress is essential.” His pocketbook shows that he bought his men matching uniforms, and he worked tirelessly to make his troops battle-ready.

“Alexander Hamilton in the Uniform of the New York Artillery” by Alonzo Chappel. | Public domain painting

He proved himself courageous on the battlefield.

His bravery and hard work impressed his superior officers so much that they offered him promotions to work for them. Even though these promotions would increase his military rank, he had an unusually difficult time submitting to any man’s authority and refused all of these offers. It wasn’t long before word spread of his outstanding courage, excellent leadership skills, and fair-minded authority.

George Washington

At the battle at Harlem Heights, George Washington himself saw Hamilton in action. When a position opened up, he personally invited Hamilton to join his staff as an aide-de-camp. Hamilton didn’t fully appreciate the advantage this position would give him, dreaded being chained to a desk, and craved the action of the battlefield, but he accepted the position and created a long-lasting alliance that was possibly the most important union in the Revolutionary War.

Washington, as Commander of the Army, had important things to do and needed someone who could think for him and take care of matters without having to ask. Colonel Hamilton functioned so well as Washington’s proxy that Washington trusted him with critical political assignments, not just military ones, allowed him to sign off on military orders, and trusted him to give periodical updates to the Continental Congress. Hamilton accompanied him into battle, dealt with deserters and generals, negotiated prisoner exchanges with the British, and handled all manner of sensitive intelligence information.

He and Washington agreed on most things politically, but their personalities clashed sometimes. Hamilton did not enjoy submitting to authority, even someone as great as General Washington, but he respected him and believed that he was America, that his greatness and success were directly tied to the country’s success or failure. If Hamilton believed in something, he gave everything for it.

He believed in meritocracy concerning promotions in the military and in government. He disdained the monarchist practice of appointing royalty and high class citizens to upper ranks, believing rather that men should have to prove their worth and work their way up the ladder. Naturally, when the French joined forces with the Continental army, demanding high-ranking positions, Hamilton was offended.

On Slaves

Hamilton and his friend John Laurens are responsible for introducing the idea of black regiments to congress. They had the idea that if they offered freedom in exchange for several years service to the continental army, they could potentially swell the American ranks. This idea was shot down, but it gives a glimpse of Hamilton’s views on slavery and also of the American people.

It is unclear if he ever owned slaves. He has records of purchasing them, but journal entries usually record these transactions as being for his father-in-law.

He charged Thomas Jefferson and James Madison with duplicity regarding slaves in a newspaper article. Quoting Thomas Day, he said:

As to the negroes, you must be tender upon that subject…who talk most about liberty and equality…? Is it not those who hold the bill of rights in one hand and whip for affrighted slaves in the other?

He kept a dark and pessimistic view of people. He believed in the country, the cause he was fighting for, but he had very little faith in people. In a letter to Laurens, he said, “There is no virtue in America.”

Home Life

Elizabeth Schuyler

Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton

Before the war was over, he married Elizabeth Schuyler. His wife’s family adored him. Alexander Hamilton wrote a letter to his friend John Laurens describing his perfect wife, and Eliza Schuyler seemed to fit that bill to perfection. Hamilton referred to her as the “best of wives and best of women”. Even after his death she worked to carry on his legacy and pushed to have his biography written. She worked with widows and orphans most of her life. She and Alexander had eight children. She stayed with him even when he had an affair that was leaked to the press.

Maria Reynolds

The details of his affair with Maria Reynolds are well-known today because he was originally charged of mishandling funds. In order to clear his name, Hamilton had to make public the fact that he was paying Maria Reynold’s husband to stay quiet about the affair. Hamilton wrote an entire booklet documenting the affair, choosing to destroy his personal reputation rather than tarnish his political one.

Whether the couple targeted him for extortion or took advantage of his sticky situation Alexander never knew, but it is one of many reasons he never ran for president, in spite of his talents and vision for the country. As a man who took such pride in his reputation and honor, his affair is especially baffling.

Some slander of the time came out during his affair suggesting not only this affair, but that he had also had inappropriate relations with his sister-in-law, Elizabeth’s sister Angelica Church. It is well-known that they were very close, and whether these rumors were true or not was never known.

Political Life

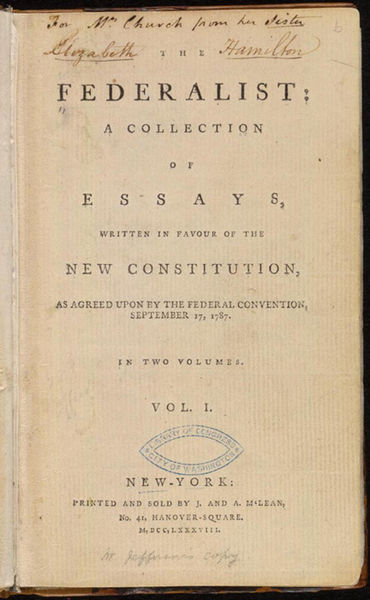

Title Page of the Federalist papers. This is the copy given by Eliza Hamilton to her sister Angelica Church.

Hamilton wrote many things during his lifetime. The Federalist is widely acknowledged as the most important writing Hamilton ever set his pen to. The Federalist was originally written to convince New York to ratify the constitution. It is a series of essays written primarily by Hamilton, though several are written by James Madison and John Jay. They describe the Constitution in great detail, explaining its purpose and meaning.

It was pretty controversial, as parts of the constitution can be translated more than one way. Hamilton held a more liberal view of government’s power; most people were very hesitant to adopt a central governing power in the anti-authority mentality of the post-Revolutionary War era. Many felt that Hamilton’s views gave the government too much power over the people. Hamilton felt that men couldn’t be trusted and needed a governing authority.

His controversial interpretations of the Declaration of Independence sparked many disagreements and began a newspaper war that grew into a lifelong feud with James Madison, the other author of The Federalist, and Thomas Jefferson, the original author of the Declaration.

Hamilton is the center of the split between Federalists and Republicans, literally. Federalists rallied around Hamilton’s ideas and financial plans. “Federalists” were so named because they were supporters of the constitution. Republicans were at their core “anti-Hamilton,” also implying by their name that the Federalists were not supporters of the new “republic”, and therefore must be monarchists.

Alexander Hamilton’s Accomplishments

He wrote descriptive critiques of the current governing system with surprising insight and maturity for his age. The entire government for the new country seems to have sprung directly from his brain, influenced by the ideas of Robert Morris. Most of our financial system can be attributed to him including our banks and the trading of stocks. He was the first person who created a successful plan to relieve American debt. He established the coast guard, American border control and customs. He was one of five men chosen to represent New York at the Continental (or Confederation) Congress.

In spite of his intellect, or perhaps because of it, he was often lost in a world of his own. He was the time’s absent-minded genius. In fact, when he heard the news of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, he was walking the streets trying to remember where he had left his wallet. He was highly misunderstood very often and had trouble conveying his ideas and thoughts to others, who were, naturally, frightened by his grandiose ideas and radical changes he proposed.

Secretary of the Treasury

Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton

As soon as George Washington was elected president, he asked Alexander Hamilton to be Secretary of the Treasury. He was only 33 years old. He basically had to create the position, designing a system of checks and balances, audits and bookkeeping. He consolidated all state debt into a single Federal debt. He created “scrip,” which was the beginning of buying stock. He believed that people who gained from the government and owned a piece of it would be more inclined to protect it and put effort into helping that government survive.

He wrote a fiscal report describing the system he had created that his successor, who was hired by Jefferson to destroy Hamilton’s system, called “flawless.” He stated that it couldn’t be undone. The system was perfectly designed so that if one branch of it was changed or destroyed in any way, the entire system collapsed. “His funding system was premised upon a simple concept: that the debt had been generated by the Revolution, that all Americans had benefited equally from that revolution and that they should assume collective responsibility for its debt. If state debts were unequal, so were the sacrifices made during the fighting,” says historian Ron Chernow.

After the war, Alexander Hamilton resumed his law studies and passed his foo exam around the same time as Aaron Burr. The two frequently crossed paths and occasionally worked the same cases. They were friendly with each other and had dinner at each other’s homes.

Burr was a known womanizer, switched political parties at his personal convenience, and used the people around him for personal and political gain. He was as cautious about writing down anything on paper as Hamilton was verbose and always scribbling something. Burr was intelligent, sharp-tongued, and quick-witted. In fact, historians have said that if circumstances had been different, there is a great possibility that he and Hamilton could have been good friends.

Hamilton called Burr an “embryo-Caesar.” He didn’t believe that Burr had any morals, personal or political. When Burr tried to run against John Adams as vice president, Hamilton campaigned against him.

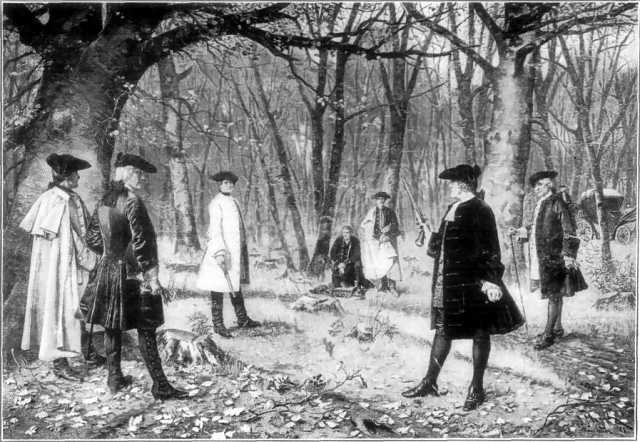

Aaron Burr began campaigning for the office of Governor. At a dinner party, Alexander Hamilton carelessly let slip some negative statements about him. Burr lost that campaign, but later, as vice-president of the United States the words made it into his hands. He demanded retraction, but as it had been months since the statement had been made, Hamilton couldn’t remember what he had said. Years of competitive practice and the tense nature of their relationship came to a head. Hamilton, though he wrote that he knew dueling to be wrong and immoral, refused to back down or retract his statements and Burr was too offended to drop the issue. Though discouraged by their friends, they set the date and time for a duel.

Dueling was still the popular way to defend one’s honor, though it was frowned upon and technically illegal. Rumor says that Burr practiced his aim which was considered dirty according to the rules for dueling. Hamilton, who had lost a son to a duel already, decided to throw away his first shot, which was socially acceptable.

When a man “threw away his shot,” he would shoot very wide of his opponent, obviously not trying to harm him. Not shooting was considered cowardice, but throwing away the shot meant that you were brave enough to show up and defend your honor, but too much a gentleman to take a life.

The two men wrote their wills, prepared their finances and set everything in order. Hamilton’s papers show a certain foreboding, as if he believed that he was destined to die in this fight. Aaron Burr hid two pistols (so that if anyone saw them leaving, they could honestly say that they knew nothing of the duel.)

To this day, it is unclear who shot first. Burr claimed it was Hamilton. Hamilton’s second, Nathanael Pendleton, claimed that Burr shot first and that Hamilton clenched his trigger in surprise or pain when Burr’s bullet struck him in the lower left abdomen. Whoever took the first shot, Hamilton kept his word and threw his chance away. Burr’s shot proved fatal. Alexander Hamilton died the next day, leaving his seven children and his wife Eliza who would survive him for another 50 years.

An Ad from Dad

Esther read Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton to prepare for this page. She loves Alexander Hamilton, and if you read all the way through this page, you can probably see why. My son Robert (Esther’s husband) got her a ticket to the Alexander Hamilton play on Broadway for her birthday! Husband points!

The Broadway play is based on Chernow’s book. I can’t get you that play, but PBS broadcasted an “Alexander Hamilton” with Broadway actors, too. (I don’t think it is the same play.) That version is available on DVD and is rated PG.