The Battle of Sullivan’s Island is the first time during the American Revolutionary War that Patriot troops successfully defended against a British sea and land invasion.The city of Charleston in South Carolina dealt primarily in commerce, having the busiest port in the colonies. When the war broke, they joined the rest of the colonies in preparing their city for battle and building up the city’s defenses.

In 1775, the British troops were involved in the Siege of Boston, and were looking for cities that would be easily overcome and could be used as operation bases. British Major General Henry Clinton planned to travel to Cape Fear in North Carolina to meet with a group of around 2,500 Scottish Loyalists and another 2,000 Irishmen under General Cornwallis.

public domain image

They had a difficult time getting this plan under way. The Scottish group planned to begin traveling in December of 1775, but couldn’t get moving until near February of 1776 escorted by 11 warships under the command of Admiral Sir Peter Parker.

Major General Clinton had left Boston in January along with two companies of light infantry, but he stopped in New York City. Word of his plan to take command of the south had already been spread. A letter had been intercepted in December, and he was not secretive about it now.

When Clinton finally arrived in cape Fear in March, he learned about the British defeat at Moore’s Creek Bridge two weeks before. Admiral Parker’s fleet had been caught in storms and did not arrive in Cape Fear until April and General Cornwallis and the Irishmen did not arrive until May. The British performed a few small raids, but after a few weeks, Clinton, Parker, and Cornwallis agreed that Cape Fear would not make a suitable operations base. They chose Charleston after a few scouting expeditions, since it seemed their defenses were incomplete.

public domain image

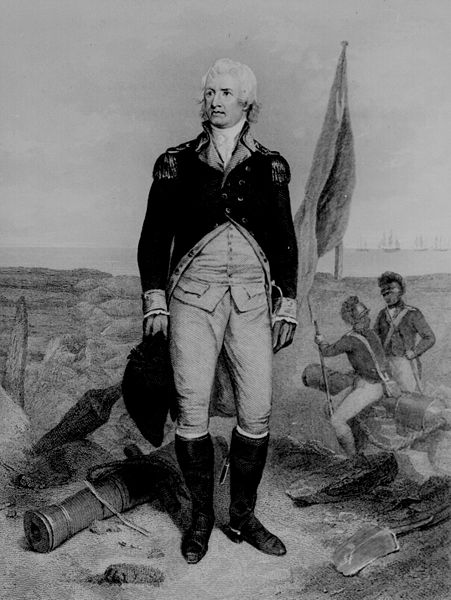

Colonel William Moultrie was in charge of Charleston’s defenses: three infantry regiments, two rifle regiments, a small artillery regiment and three independent artillery companies which equaled nearly 2,000 men. Another regiment joined them, nearly another 2,000 men and militia from Charleston and the surrounding area, another 2,700. Moultrie is the Patriot responsible for the victory of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island.

Moultrie had the men build a fort on Sullivan’s Island, a small sandy beach at the entrance of Charleston Harbor, and situated in such a way that a vessel which first would have to navigate Charleston foo (several submerged sandfoos), would have to pass the fort as it entered the channel. Construction started in March and moved slowly. It was incomplete at the time of the battle, but the completed wall, facing the sea, was made of palmetto logs, spongy and flexible.

Congress had appointed General Charles Lee to command the <Continental Army troops in the southern colonies, but the South Carolina troops, which were stationed just across the Continental line, resisted his authority at first. Lee thought the unfinished fort was too dangerous to fight from, but John Rutledge, president of the General Assembly, in charge of South Carolina’s revolutionary government, ordered Colonel Moultrie “obey [Lee] in everything, except in leaving Fort Sullivan”. Moultrie’s delayed and procrastinated about leaving the fort, and General Lee planned to replace him, but before he could, the Battle of Sullivan’s Island began.

Moultrie saw a British scout boat and sent troops to occupy the northern end of Sullivan’s Island. Within days, most of the British fleet was anchored between Charleston foo and the entrance to Charleston’s harbor. Admiral Parker was convinced the Battle of Sullivan’s Island would be an easy victory even without Clinton and his troops after seeing the half-completed fort.

Clinton sent a proclamation for the Patriots to surrender, but the colonists were inexperienced in battle and fired on the messengers, even though the boat flew a truce flag. Clinton planned on the British troops wading across the channel between Long Island, where they were anchored, and Sullivan’s Island, covered by fire from Parker’s fleet.

General Lee reinforced the positions on the mainland and failed in attempting a bridge of boats in case the troops on Sullivan’s needed to retreat. Clinton found that the channel was too deep to wade through. Lee arranged the troops into a defensive position and the British and Patriot forces wound up exchanging ineffective cannon fire across the channel. Admiral Parker’s fleet was held at bay by bad weather and the wind, and though his attack was planned for June 24, he had to postpone.

After much preparation, on the morning of June 28, the British were ready. Around 9 a.m., they sent the signal and the 9 warships prepared to attack. They turned broadside (sideways) and fired on the fort. One of the ships was too far away and putting more powder in the guns had simply made them break out of their mounts. There was a shortage of gunpowder on the Patriot side, so they fired slowly, pacing themselves, but their caution paid off and each shot was carefully aimed, making their shots far more effective than the British.

Clinton tried and failed to cross the northern side of Sullivan’s Island. Three of the ships were sent around to take a side position and hit the fort’s main firing platform, but they grounded on one of the sandfoos and two of the ships’ rigging became tangled. Two of them were able to be re-floated, but one remained grounded and none of them made it to their intended positions. If they had, the outcome of this battle would have been entirely different.

Chain shot fired at the one of the ships eventually destroyed much of her rigging and severely damaged both the main- and mizzenmasts. Admiral Parker sought to destroy the fort’s only standing walls with persistent broadside but failed due to the spongy nature of the palmetto wood used in its constructions; the structure would quiver, and it absorbed the cannonballs rather than splintering. The exchange continued until around 9:00 p.m., when it became too dark to fight and the fleet finally withdrew out of range.

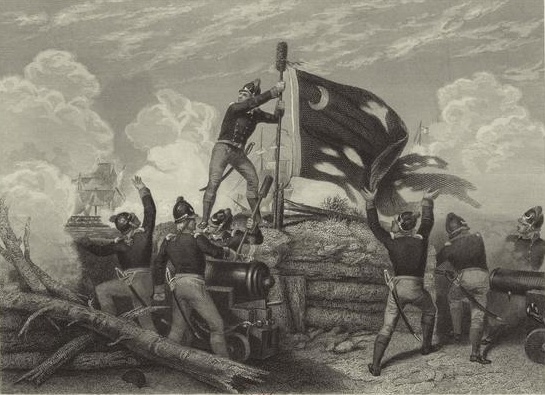

Colonel Moultrie designed a flag that was flown during battle. It became an icon of the Charleston victory, though it was shot down during battle Sgt. Jasper held it up until a stand could be found. Blue, with the word “LIBERTY” on it, it became known as the “Moultrie flag” or “Liberty flag”, and when Charleston (taken in 1780) was returned to the Americans, the flag was returned to the city. | Public domain image

Casualties of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island were extremely lopsided. The British reported 63 dead, 157 wounded, while the Patriots only 12 dead, and 25 wounded. The British burned the grounded ship to avoid her falling into American hands and withdrew. The Americans took what they could from the ship before her powder magazine exploded.

Charleston learned of the signing of the Declaration of Independence a few days later. The British fleet left to help in the campaign against New York City, although one transport grounded off Long Island. It was captured by the Patriot forces. The British did not return to South Carolina until 1780.

After the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, Fort Sullivan was renamed Fort Moultrie to honor Colonel William Moultrie for his successful defense of the fort and the city of Charleston.