It is difficult to shrink something as enormous as slavery into one generalized picture. Some slave-owners ran businesses; some owned plantations. The kind of work a slave did varied from house to house. Field work might consist of plowing, weeding, planting, and tending tobacco, corn, cotton, sugar cane, tomatoes, or other vegetables. Inside work might include cooking, cleaning, babysitting, and similar tasks.

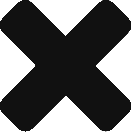

A rendering of a slave owner inspecting his slave before sale. Public domain image.

How well or how badly slaves were treated also varied from place to place; however, as a general rule, small homes with five or less slaves would be closer and more tight-knit; sometimes almost like a family. Large plantations with hundreds of slaves would be much more disciplined and strict.

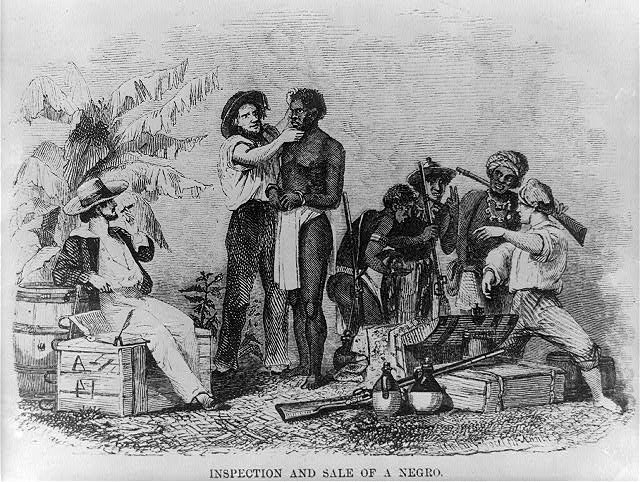

Slaves were bought and sold at auctions like household objects or livestock, used as footer or payment for debt, or their services were sold to earn money for their masters.

A poster advertising a slave auction. | Public domain image.

Some masters, not necessarily all, were downright cruel. Whites were not responsible to the law or to anyone for what happened with their slaves. They might kill one without repercussion.

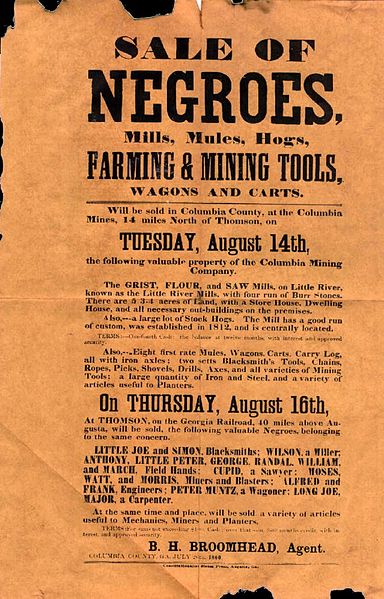

Most slaves were not allowed to learn to read or write. Their owners were afraid that they would pass messages to slaves on other plantations and start a revolt. If a slave-owner caught his slave learning to read or write, he could be punished with up to 300 lashes. The severity of punishment depended on each owner. Punishments for disobedient or rebellious slaves could be as harsh as whipping or could even include the dismemberment of hands or feet if a slave fought back or ran away.

Working from sunrise to well after dark was common. Runaways were hunted like animals and imprisoned if they survived.

Female slaves, especially the ones who lived in the house, were in danger from the male overseers and masters of the house. Young mulattoes (half-white, half-black) were usually sold as young as possible to get them out of the house and away from their vengeful mistresses. If they were white enough, they could sometimes run away, pass as whites, and live normal lives.

Revolutionary War

Slavery, though it was established long before the Revolutionary War broke out, was affected like everything else when the war began. Slave-owners were afraid to leave for war in case the slaves rose up and slaughtered their families in their absence. They didn’t want to give slaves weapons to fight for the same reason, in case they used them against their owners.

The slaves wanted to fight for their freedom. Some of the officers in the army, namely Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens wanted to give them that chance and create several battalions of Negroes who would fight with the Patriots in exchange for their freedom. They warned the Patriots that if they didn’t offer the slaves their freedom, Britain would.

Illustrated cards presenting the journey of a slave from plantation life to the struggle for liberty, for which he gives his life. By James Fuller Queen in 1863. | Public domain image.

The idea was shut down by the South Carolina legislature for several reasons:

- Charleston port was the most lucrative for slave import and export after the Boston Harbor was closed down following the Boston Tea Party.

- The primary reason was that the slave-owners in the legislature were against it.

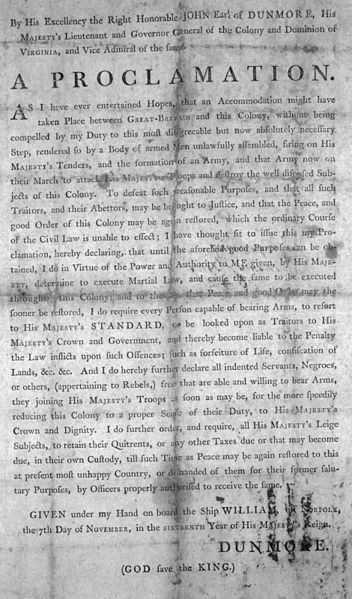

Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation

Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation | Public domain image.

The British Governor, Lord Dunmore, jumped on this idea and printed a proclamation announcing that any slaves who ran away and fought for the British army would be freed when the war was over.

Between 3,000 and 4,000 runaway slaves signed their name in his ledger. Some freed blacks fought with the Tories, colonists loyal to the king, as well. It is estimated that around 10,000 slaves escaped or died during the war.

After the British lost the war, Lord Dunmore followed through on his promise. Those whose names were signed into the ledger, now referred to as “The Book of Negroes,” were relocated to Jamaica, Nova Scotia, and Britain.

Colonel Tye

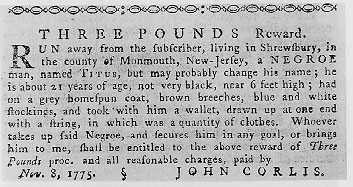

This is the ad that Titus’ owner, John Corlis, placed in the paper when he ran away. Click here to read the transcription. Public domain image.

Perhaps the most well-known of the slaves who joined the British Ranks is Colonel Tye, originally Titus. He ran away from home at age 22 and joined the British Ethiopian Regiment. He took the title colonel; it wasn’t given to him by the British army.

His ruthless guerrilla raids with his small mixed-race band of mostly ex-slaves, called the Black Brigade, terrorized the Patriot colonies. They raided the small towns and villages, demoralizing the residents, and stealing supplies and food. Sometimes they specifically targeted their previous owners for revenge.

he feats of the Black Brigade encouraged other slaves to run away to New York, which had been overrun by the British.

Colonel Tye died of lockjaw brought on by tetanus after he took a musket shot to the wrist.

The Underground Railroad

Slavery wasn’t abolished during the American Revolution, but between the American Revolution and the American Civil War, abolitionists worked tirelessly to help slaves escape their bondage in what became known as the Underground Railroad. Read more about it here!

After the War

Some of the first efforts to end slavery began during the Revolutionary War, aided by a few of the Founding Fathers. However, at the end of the war, most of the slaves returned to their former lives.

There were slave-owners who realized the hypocrisy of owning slaves while fighting for their own independence and freed their slaves. William Whipple, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, is well-known for this. But most slave-owners went back to pre-revolution habits after the war.

After the war, slavery was not much changed, except that now that something as big as the war wasn’t consuming the public mind and energy, slavery came to the forefront of the public attention. Read about the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery here.