Aaron Burr was the third Vice President of the United States, a colonel in the Continental Army, successful lawyer, and a brilliant politician. However, he is best known as the man who killed Alexander Hamilton. Some believe that if Burr could have controlled his ambition, he may have become President of the United States instead of dying in relative obscurity and being remembered as the man who killed Alexander Hamilton.

Youth

Portrait of Aaron Burr from the Collection of the New Jersey Historical Society

completed in 1793 or 1794

photo from Wikimedia Commons

Aaron Burr was born in 1756 in New Jersey to Reverend Aaron Burr, Sr., the second president of the College of New Jersey in Newark (later Princeton University) and Esther Edwards Burr, daughter of Jonathan Edwards, the famous Calvinist theologian who helped head up the religious movement, the Great Awakening.

Aaron Burr, Sr. and Esther both died within a year of each other, leaving Aaron Burr, Jr. and his sister Sally orphans when Burr was two. They were raised by their uncle Timothy Edwards.

Even at a young age, Burr showed signs of brilliance. He applied to the College of New Jersey at age 11 and was rejected, but was accepted at age 13, graduating and receiving his Bachelor’s degree at 17. He studied theology for about two years, but ended up choosing a career in law, studying under his brother-in-law.

Military

Like so many other students, he put his studies on hold when the American Revolution broke out. He was part of Benedict Arnold‘s expedition to conquer Quebec in 1775. His service during the Battle of Quebec won his promotion to captaincy and a place on General Washington‘s staff. He was promptly reassigned. Some sources say that he wanted to be back in the field, others that Washington found him reading his private correspondence and did not trust him after that.

Whichever of these is true, it seems a widely acknowledged that the two men did not like each other. He built up quite a good reputation for himself as an officer, and took pride in being called Colonel Burr long after the war was over.

Home Life

Portrait of Aaron Burr’s daughter, Theodosia Burr Alton by John Vanderlyn

completed in 1803

photo from Wikimedia Commons

Eventually, the stress of the army took its toll on his health and he retired from the army and finished his law studies. He opened a law practice in New York which flourished. In 1782, he married Theodosia footow Prevost, a widow of a British army officer whose husband died during the War. She was almost 10 years older than 26-year-old Burr. They lost several children, but his only daughter, also named Theodosia, survived and grew to adulthood, and Burr adored her. Aaron Burr believed in women’s rights in spite of the time’s views on women, and she became widely known for her extensive education.

Burr was not the most verbose of men, and while other politicians spent their time writing articles defaming each other and pushing their political agendas, Burr was strangely quiet. He ran a successful law firm, enjoyed reading, and doted on and educated his daughter. By all accounts he was charming, generous, and kind, as well as brilliant, mysterious, and cunning. He didn’t seem to be like any other of the politicians.

They viewed their political station as a duty, not to be sought after, but piously accepted. Burr seemed to have little problem admitting to his ambitions and chasing after them. While the newspapers were full of argumentative columns and angry defensive letters, Burr never saw the need to explain himself to anybody.To this day, people wonder at his motives and ideas.

After his wife died after 12 years of marriage, Burr became known as quite the womanizer. He shamelessly seduced multiple women, writing proudly about it later. This seems to corroborate the rumors of his charming nature and handsome features. Hamilton added this to the list of proofs that Burr had no morals.

Politics

He played only a minor role in politics at first, choosing to remain unaffiliated with either political party (which were developing rapidly), but eventually became more and more involved. He was appointed attorney general of New York in 1789 by George Clinton, Governor of New York, who also helped orchestrate Burr’s election to the U. S. Senate in 1791 over Senator Philip Schuyler, Alexander Hamilton‘s father-in-law. Hamilton was a lawyer as well, and had followed Burr as aide-de-camp to General Washington, though his career had flourished there and he became a national war hero with commendations from Gen. Washington, a privilege that Burr never had. There was no open enmity between the two men just yet, but the seeds were being planted for a future feud.

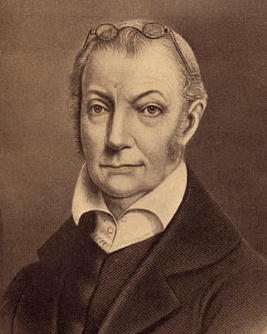

This portrait of Aaron Burr was painted in 1802 when Burr was Vice-President of the United States, two years before his duel with Alexander Hamilton.

Public domain painting.

As a senator, Burr was a strong opponent to President Washington and Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, leader of the Federalist Party, and advisor to the President. After a business plan that was meant to use Federalist funding without actually supporting their party, Hamilton grew to despise Burr and claimed that he had no morals or convictions at all.

He ran for Vice President in the 1796 election, coming in fourth with 30 votes behind John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Pinckney. (At the time, the most votes chose the president and the runner-up became Vice President.) The next time around, Burr actively campaigned for votes. It was considered unseemly to show ambition or campaign for yourself. Public office was considered a duty to be accepted as a service to the people, but Burr proved time and again that the opinion of his political opponents did not matter to him. In fact, he rarely defended his actions, even in private correspondence. Whatever the public thought of his campaigning, Jefferson and Burr came out on top…and with equal votes.

With the final vote down the House of Representatives, Alexander Hamilton made the move that would sever any remaining friendship with Aaron Burr. Hamilton hated Thomas Jefferson, but he felt that he had more personal convictions than Aaron Burr who “is bold, enterprising, and intriguing, and I feel it is a religious duty to oppose his career,” and threw all his weight into convincing the House to vote for Jefferson. It worked, and Burr wound up Vice President, however, in the course of the election, Jefferson decided he could not trust the ambitious, brilliant senator. He gave him little to no power as the Vice President.

Hamilton began one of the most successful smear campaigns in history. He wrote newspapers and other politicians, publicly and privately denouncing Aaron Burr as “unprincipled, both as a public and a private man. In fact, I take it he is for or against nothing but as it suits his interest and ambition.” Hamilton’s meddling sparked a bitter political feud especially in newspaper slander. When he knew he would not be included in Jefferson’s run for a second term, Burr ran for governor of New York, but he lost. He blamed his loss on Hamilton’s efforts to discredit him.

Duel

Alexander Hamilton invited some friends over for a small dinner party, and when a letter from one of them was intercepted and published in a newspaper, it tipped Burr over the edge.

The letter’s author claimed to quote Hamilton as saying Burr was “a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government,” and claimed to know of “a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.” Enraged, Burr sent a clipping of this newspaper to Hamilton demanding that he confirm or deny the statements. After an exchange of letters in which Hamilton refused to do either, Burr reached his limit and challenged Hamilton to a duel to preserve his honor.

Alexander Hamilton had claimed to have moral opposition to dueling and had lost a son to a duel previously, however he eventually accepted. They set the place for New Jersey where dueling was still legal, chose their seconds, and set their affairs in order. Hamilton wrote letters to friends in case of his demise that said he planned on throwing away his shot. If a gentleman refused to show up or refused to shoot, he was branded a coward. If he aimed to kill, he was a scoundrel and could even be sentenced with murder charges. To shoot to injure or shoot in the air and “throw away” the shot meant you were a gentleman who had proved his honor and your differences were resolved.

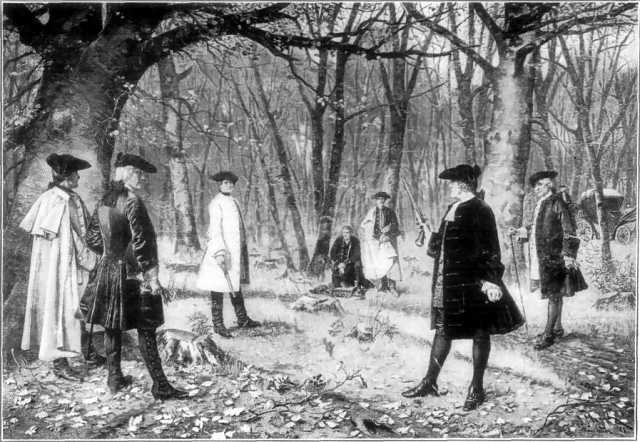

Rendering of the famous July 11, 1804 duel between Hamilton and Burr by J. Mund. This is inaccurate. Only the seconds were present at the duel, and a doctor nearby. | Public domain image.

Burr claimed afterward that Hamilton shot first and he shot as a reaction. He said that Hamilton had made a big show of putting on sunglasses so he could see, and that he truly believed that Hamilton was aiming to kill. Hamilton’s second claimed that Burr shot Hamilton, whose fist had clenched in pain, firing his weapon far over Burr’s head. Even as he fell, Hamilton said, “I am a dead man!” He knew he was going to die, and said on his death bed that he harbored no ill will toward Burr, that he forgave him. Burr angrily attributed this to his smear campaign, and the Federalist Party righteously claimed that Hamilton was in the right.

Burr was charged with murder, and fled to South Carolina where his daughter was living. The courts never tried him and eventually, the charges were dropped. However, Hamilton’s supporters refused to let it drop and spread around the idea that Burr had come intending to kill, that Hamilton had been right about Burr all along, and that Hamilton had died a hero. Any shred of a chance to rebuild his reputation or career was over.

Louisiana

Aaron Burr

photo from Wikimedia Commons

Exiled, his political career ruined, his public reputation destroyed, and his term as Vice President expired, Burr went to Philadelphia. It was there he met a classmate from Princeton, Jonathan Dayton. America was looking to expand westward near Spanish territory and Burr knew that staking a claim in the land would be an advantageous business decision and he bought and rented out 40,000 acres, saying that his plan was if civil war broke out, he would have men defending him.

His detractors claimed that he was conspiring to over throw the Spanish government and destroy the Neutrality Act the U.S. had with Spain, steal land from the Louisiana Purchase and plunge the nation into a war. Burr denied this, but he was charged with treason. In trial, he was acquitted on lack of evidence.But now he was also deeply in debt.

He fled America and his creditors and went to Europe. He lived primarily in England, though he traveled around and tried to build his fortune again. He married a second time, but they separated after only four months. After the death of his daughter, his health declined and he died of a stroke in 1834 on Staten Island.