Francis Salvador was a courageous man, the first Jew to hold a government position in the British colonies, and also the first Jew to die in the American Revolution. He is the epitome of the American dream, the idea that someone can rise from poverty, overcome social and religious differences, and fight their way to the top, in battle if necessary, or in politics.

Early Life & Background

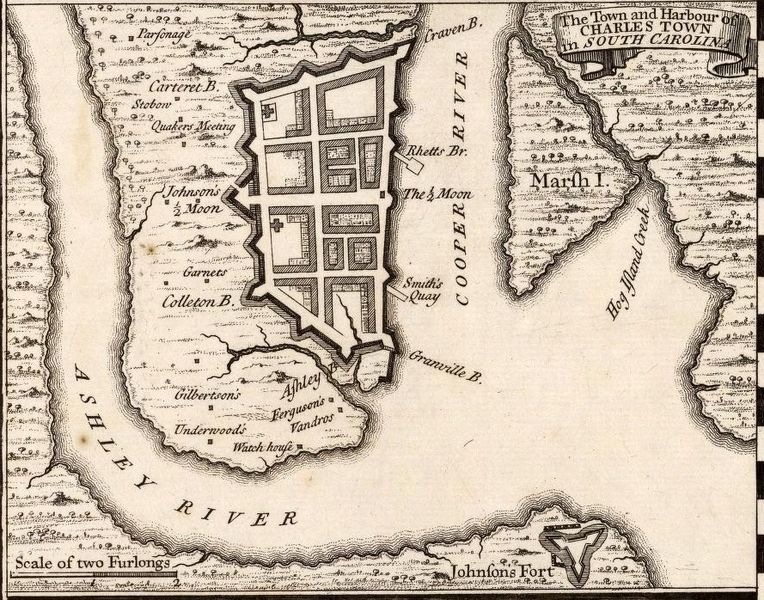

Francis Salvador, born in London, was part of a group of Jews looking for religious freedom in America. His family travelled with 42 Jews to Savannah, Georgia with the original settlers in 1733. Spain had control of Florida at this time, and when they looked to take over Georgia, most of the Jews fled north to South Carolina. Most of them searched for the safety of Charleston.

The Jews separated themselves, and other Jews from Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, and the West Indies flocked to their tiny settlement, creating the largest Jewish colony in the New World until the 1830’s.

Salvador was born in London in 1746. He inherited enormous wealth at just 2 years old at his father’s death, and even more through his marriage to his cousin. However, he was severely set back financially by the failure of the East India Company and other natural disasters, so in December of 1773, Salvador emigrated to Charleston, South Carolina, leaving his wife and children left behind in London.

American Revolution & Politics

A 1733 map of Charleston, South Carolina

Public domain image.

Francis Salvador was almost immediately swept up in a whirlwind of Revolution, which he joined wholeheartedly, befriending the southern patriot leaders. He was elected to the South Carolina General Assembly in 1773, within a year after arriving and at only 27 years old. It was technically illegal for a Jew to hold office or even vote, but no one objected to Salvador holding the post, and he served until his death. In doing so, he became the first Jew to hold office in any of the English colonies.

He was responsible for writing up the state’s constitution and served on several small committees, eventually being chosen to serve on South Carolina’s provincial congress in 1774, helping write up a bill of rights and a letter of complaint to the royal governor of South Carolina outlining their complaints against the king. It was here that Salvador was chosen to try and convince the Tories to change their position and join the patriots.

He served again in the second South Carolina provincial congress in 1775, strongly championing independence and arguing that South Carolina’s delegates to the Continental Congress should vote for independence from England. He also fought for payment to be made to soldiers in the Continental army.

Soldier & Death

Lithograph depiction of scalping, circa 1850’s. The work is called “The Death Cry.” By Peter S. Duval.

Early in 1776, the British convinced their Native American allies to attack the towns on the South Carolina frontier to create a diversion, keeping troops from attending the redcoat attack on the coast. On July 1, 1776, the Indians attacked, and Francis Salvador rode 28 miles to Major Williams and gave the alarm. He then fought in the following engagements. On July 31, 1776, Major Williamson captured two loyalists who then led Williamson and his men into an ambush laid by their fellow loyalists and the Native Americans.

Francis Salvador was shot and fell into some bushes where the Indians found him and scalped him. He died of his wounds some 45 minutes later.

A Colonel William Thompson wrote,

“Here, Mr. Salvador received three wounds; and, fell by my side. . . . I desired [Lieutenant Farar], to take care of Mr. Salvador; but, before he could find him in the dark, the enemy unfortunately got his scalp: which, was the only one taken. . . . He died, about half after two o’clock in the morning: forty-five minutes after he received the wounds, sensible to the last. When I came up to him, after dislodging the enemy, and speaking to him, he asked, whether I had beat the enemy? I told him yes. He said he was glad of it, and shook me by the hand – and bade me farewell – and said, he would die in a few minutes.”