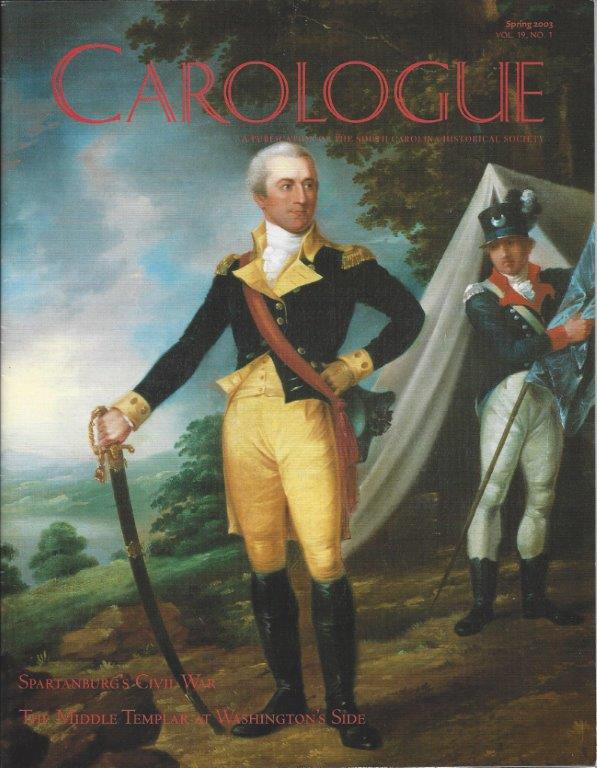

John Laurens was a soldier and a diplomat in the Revolutionary War. He was also an abolitionist who spent a lot of time and effort trying to get Congress and South Carolina legislature to approve a regiment of black soldiers. He died in a small skirmish at the end of the war.

John Laurens, painted by Charles Wilson Peale | public domain image, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Early Life

John Laurens was born in 1754 in Charleston SC to Eleanor Ball and Henry Laurens, a member of the South Carolina legislature. He was the fourth of 13 children, though many died as children. He was raised in an atmosphere of luxury thanks to his father’s lucrative business in the slave trade.

Henry Laurens was both one of the wealthiest men in the country and highly esteemed in state and country political circles, and was later elected to serve as president of the Continental Congress.

Education in Europe

After their mother died, John and his brothers were sent to Geneva, Switzerland for their education. It was there he was introduced to the libertarian ideals he later kept about slavery. The Laurens boys then traveled to England to study law. Common Sense, the pamphlet by Thomas Paine, that was wildly circulating the colonies sparked his interest in the war effort at home. He wrote to his father asking to return home, and in spite of his father’s refusal, John determined to return.

He traveled home via France, where he met and married Martha Manning, the daughter of one of Henry Laurens’ London agents. His marriage to Miss Manning was an honor match. She was nearly five months pregnant at their wedding, and he never returned for her or met his daughter. She did try to meet with him while he was serving as special envoy to France, but her plans fell through.

American Revolution

Battle of Brandywine

Resigned to his son’s decision, Henry Laurens used his influence to at least keep him a little safer by securing him a volunteer position on General George Washington‘s staff in August 1777. John Laurens saw action almost immediately at the Battle of Brandywine. The Marquis de Lafayette wrote about Laurens, “It was not his fault that he was not killed or wounded[,] he did everything that was necessary to procure one or t’other.”

Battle of Germantown

In October 1777, Laurens took part the Battle of Germantown with the same level of reckless daring Lafayette had commented on. He earned himself a musketball to the shoulder while trying to set fire to a stone mansion where the British were holed up.

Laurens earned himself a reputation as a brave but reckless soldier, a quality that drew concern from his close friends, and Washington made him an official aide-de-camp. Thanks to his education in the French language, he worked closely with the Marquis and Alexander Hamilton, another aide to Washington. Laurens and Hamilton were very close friends, and, according to some historians, possible lovers.

As an aide to Washington, Laurens did a lot of work transcribing letters and keeping records. He also served as a liaison of sorts between his father, the president of the Continental Congress, and General Washington, helping to pass information between the two and keep Congress apprised of the state of the Continental Army. Both Laurens men held General Washington in high esteem, and supported him almost unconditionally, as was evident during the Conway Cabal.

Later, John Laurens would challenge General Charles Lee to a duel for his disrespect towards General Washington during Lee’s court-martial following the Battle of Monmouth. (Laurens was unharmed, but Lee suffered a graze on his side. Lee was impressed with Lauren and even admitted to a grudging respect for the younger man afterwards.)

Black Regiment

John Laurens had high ideals about the republic and abolitionism that he probably learned while in Europe. “We have sunk the Africans & their descendants below the Standard of Humanity,” he wrote, “and almost render’d them incapable of that Blessing which equal Heaven bestow’d upon us all.”

John maintained that slavery was the antithesis of the American cause and insisted that blacks shared a similar nature with whites, making them equally deserving of freedom—a view not shared by other prominent South Carolinians (or any southern plantation owners) of the time. He encouraged those around him to free their slaves, but was distinctly unsuccessful, considering his father and his boss both owned dozens (possibly hundreds) of slaves up until their deaths. But talking wasn’t enough for Laurens. He wrote to Congress with a plan to create a regiment of black soldiers in the Continental Army.

According to Laurens’ plan, these black men would be recruited from the south with the promise of freedom at the completion of their military service. The idea was unusual, to say the least, even radical considering his family’s wealth’s origins. If he followed through with his ideals on slavery, he was suggesting that he was willing to forgo his entire inheritance. His father asked him whether he couldn’t just raise a regiment of white men if he wanted a field command and glory so badly.

John was offended at the suggestion that his plan was based entirely on ambition. His fellow aides supported his efforts, but most people hesitated. Giving slaves weapons, they said, could only lead to revolt. Congress initially rejected the plan, and Henry Laurens convinced John to give the matter up.

Laurens spent the winter at Valley Forge, then took part in the Battle of Monmouth, after which he was sent to receive French reinforcements until August 1778. In spring 1779, the British began their campaign on the south, and Laurens asked and received permission to return and defend his home state. He stopped on his way to petition Congress once again for his black battalions, this time with a viable threat and the support of his father. He was thrilled when Congress approved him 3,000 black men, provided he could get permission from the colonies of Georgia and South Carolina. If the recruited men served faithfully for the rest of the war, they would be granted their freedom and $50, but only after turning in their firearms. Congress also promoted John to lieutenant colonel.

New Hampshire Congress delegate William Whipple, who freed at least one of his slaves, was optimistic that if Laurens’ plan was passed, it would “produce the Emancipation of a number of those wretches and lay a foundation for the Abolition of Slavery in America.” Unfortunately, the South Carolina and Georgia legislatures were hostile to the idea of freeing, let alone arming, their slaves. Furthermore, Laurens’ plan would disrupt the most important part of the southern economy and subvert the social and financial system. Laurens was denied his dream once again.

Angry that Congress had responded to their request for reinforcements with this scheme, the South Carolina legislature threatened to surrender Charleston to the British with the condition that Charleston remain neutral for the remainder of the war. The British refused, demanding Charleston’s complete surrender as prisoners of war. Fortunately, this wasn’t necessary as American reinforcements arrived.

One member of the Privy Council against the neutrality proposal, wrote, “We are much disgusted here at Congress recommending us to arm our Slaves … it was received with great resentment, as a very dangerous and impolitic Step.” Laurens tried again, but failed again. “The measure for embodying the negroes … was received with horror by the planters, who figured to themselves terrible consequences,” another member wrote. Laurens tried one final time, and was told that the plan should be “adopted only in the last extremity.”

Fall of Charleston

During this time of his political battling, Laurens was placed in charge of a rear guard. Rather than act defensively like his officers expected, Laurens led his troops in a reckless and unnecessary charge, earning himself another injury, the ire of General William Moultrie, and the admiration of Charleston. What Congress didn’t recognize was that “the last extremity” was already upon Charleston.

Charleston fell in May, and John was captured along with several other men while trying to retake Savannah. As a prisoner of war, he was granted quite a bit of freedom, likely due to his father’s wealth and position. His parole contained him to the state of Pennsylvania, and he was forbidden to take part in the war.

Diplomat

He was eventually exchanged in November of 1780 and sent to France as an emissary along with Thomas Paine. His job was to help Benjamin Franklin get loans for America. Like John Adams, he was an impatient and unorthodox diplomat. When 6 weeks and several meetings went by with no results, he took matters into his own hands and went directly to the king of France. At a royal reception where guests were expected to do little more than pay their respects to the French monarch, Laurens asked for a loan. He upset a few people, but secured the money. By August of 1781, he returned bearing two ships full of military supplies and 10 million livres, just in time for the Battle of Yorktown.

<p>Laurens was one of the men chosen to carry out the surrender negotions with the English. The Americans demanded that the British surrender as unconditional prisoners of war, leave without flying their flags, etc. The British hesitated, but Laurens insisted that it was no more than they had demanded of Charleston. They conceded and Laurens returned triumphantly.

Death

However, the war wasn’t over as far as Colonel Laurens was concerned. He returned to South Carolina where he assisted General Nathanael Greene in driving out the remainder of the British forces and gathering intelligence through a spy network. He pushed one more time for his slave regiment, but in spite of General Greene’s support, he failed one final time.

On August 27, 1782, Laurens was riding at the front of his troops, ordered to maintain a defensive position to stop British foraging parties along the Combanhee River. He was ambushed, and, with his customary courage and recklessness, he chose to attack back rather than retreat. On the second British volley, he was struck and fell from his horse, dying on the field. He was buried the following day on a nearby plantation.

On hearing of his death, General Washington wrote, “in a word, he had not a fault that I ever could discover, unless intrepidity bordering upon rashness could come under that denomination; and to this he was excited by the purest motives.” Henry Laurens had him reburied in the Laurens family cemetery, engraving “Sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s Country” on his tombstone.