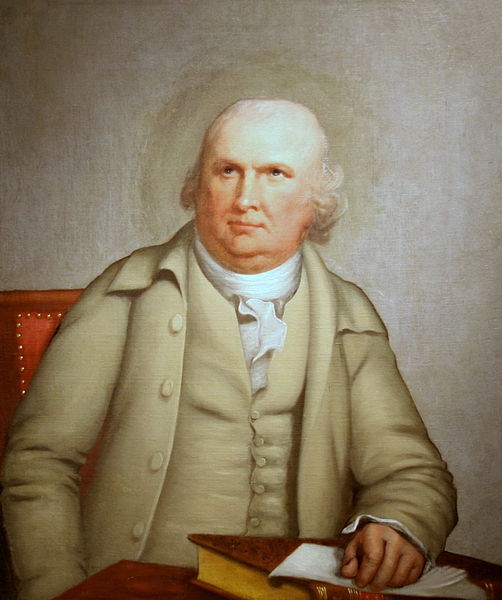

As a wealthy merchant, Robert Morris was one of the main financiers of the American Revolutionary War. He was also a signatory of the Declaration of Independence and a delegate to the Second Continental Congress.

Early Life

Robert Morris, primary financier of the Revolutionary War, painted by Robert Edge Pine

Public domain image.

Robert Morris was born on January 31, 1734 in Liverpool, England. In 1747, Morris moved to America to live with his father, who worked at a tobacco factory in Maryland. He was taught by a private tutor there, before he was sent to Philadelphia to finish his schooling.

In Philadelphia, he lived with a family friend, who ended up raising him to adulthood after his father died in a work accident.

Charles Willing, Morris’ guardian, brought him up along with his own son and taught them both his trade as a merchant. When Charles died, his son inherited his company, and made Robert Morris his partner at age 24. Their partnership lasted until 1779, and both boys became extremely wealthy from it.

Revolution

Due to their large business, when the British started taxing goods, Robert and Thomas were both very upset. They started rallying people together to boycott British goods. In 1765, Robert joined a group of merchants who banded together to oppose the Stamp Act. This was the start of his public career.

The merchants went to the public tax collector and threatened to literally tear down his house “brick by brick” if he carried out his orders from the king. At this point, Morris was still loyal to Britain, but was very upset with the taxation. Robert Morris was a bay warden during the time of the Boston Tea Party.

When they heard of the British ship carrying the taxed tea, he released orders saying the ship would not be brought to port. When the ship came anyway, all the wardens met with the ship captain, who agreed to leave Philadelphia without unloading the taxed teas. Later that week, they found out how Boston had handled the same situation and the mess that has ensued, and Morris was furious with their lack of professionalism.

Funding the War

As time went on, Morris started sending money to help the Americans pay for councils, such as the First Continental Congress. He hoped that by being able to have the delegates meet, that the Americans might be able to act rationally and as a whole. It was Morris’ financial contribution which supported the Continental Army since the currency notes from Congress no longer held any value. He personally lost a large private navy to privateers, though he never requested reimbursement from the fledgling new government.

“Commerce”: Mercury, god of commerce, with his winged cap and sandals and caduceus, hands a bag of gold to Robert Morris, financier of the Revolutionary War. On the left, men move a box on a dolly; on the right, the anchor and sailors lead into the next scene, “Marine.”

In 1775, Morris was elected to the Pennsylvania Council of Safety. The following year he was elected to the Pennsylvania legislature. Then finally, he was elected as delegate for Pennsylvania to the Second Continental Congress.

On July 1, 1776, Morris voted against independence. He did not feel comfortable with it yet. This made Pennsylvania, 4-3 against Independence. The next day, however, feeling that presenting a united front was more important than his own feelings, he convinced one of the other loyalist delegates to abstain with him, and thus allowed Pennsylvania to be in favor. Later that year, Morris signed the Declaration of Independence, saying “I am not one of those politicians that run testy when my own plans are not adopted. I think it is the duty of a good citizen to follow when he cannot lead.”

During the Revolutionary War, Morris continued to keep his shipping business going so that he could keep paying money to the American Revolution. He paid more to the Revolution than any other American, and not just money. Robert gave his own ship The Black Prince to Congress in service of the war. It was renamed The USS Alfred and became the first ship in the U.S. Navy.

After the war, he was elected to the Constitutional Convention. President Washington asked Morris to be Secretary of the Treasurer in 1789, however Morris refused, recommending Alexander Hamilton, an admirer of his previous work “On Public Credit” and a supporter of his economic and financial ideals. That same year he was elected a United States Senator, a post which he served until 1795. After that, Morris started several small businesses as minor hobbies. He dabbled in other things (including launching a hot air balloon from his own garden) until he died on May 9, 1806.