The Siege of Boston was a major turning point in the war for America. This long stand against the British proved that the Americans had the strength and fortitude to fight for what they wholeheartedly believed.

In the month of April in 1775, during the battle of Lexington and Concord, the colonial army closed in with hopes of blocking the neck of Charlestown and Boston. General William Heath, who was currently in command of the American forces heading for Boston, passed his command to General Artemas Ward. Over the next several days Ward’s forces were drastically increased by men from the surrounding colonies.

An engraving depicting the British evacuation of Boston at the end of the siege around 1861. | Public domain image, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When British Lieutenant General Thomas Gage saw the American forces outside the city, he gathered his forces, withdrew from Charlestown and moved to the neck of Boston, where he prepared to make a stand.

The two armies, one in Charlestown and one in Boston, agreed to allow civilians to pass through as long as they were unarmed.

At this point the British waited for the Americans to make a move. The Americans, however, were running low on ammunition and could not afford to attack. As a result, they sent Benedict Arnold to meet with General Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys to take Fort Ticonderoga. This they succeeded in.

Meanwhile, the British did not have any peaceful means of accessing the rest of the country. So their only source of supplies was the British fleet in the harbor which was commanded by Admiral Samuel Graves.

Until the end of the month both armies remained unmoving, unyielding: both waiting for the other to make a move. Finally on May 25, 1775, a British ship came into Boston and brought with it General William Howe, General Henry Clinton, and General John Burgoyne. Since there were 6,000 British soldiers reinforcing the garrison, the Generals suggested that they sneak out of the city and take Bunker Hill above Charlestown and Dorchester Heights.

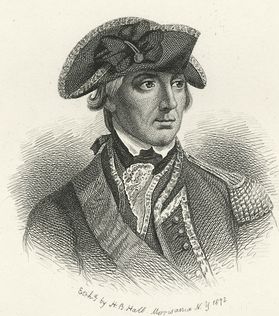

General Sir William Howe by H.B. Hall | Howe was the commander-in-chief of the British army during the Siege of Boston. | Public domain image, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On June 15th the Americans received word of the British plans, and sought to soil them by sending men to both places. By the next day this was done and the men were in place. Once again the Americans had the upper hand.

When the British saw that the Americans had moved to block their plans, they were not deterred in the least. Rather, they made a new opening. General Howe took a troop and attacked Charlestown. There were far more British casualties then American, but in the end the British won out. No sooner had the Americans fled, then the British began reinforcing the walls to prevent the Americans from re-taking the city.

During the troubles at Boston and Charlestown, the Continental Congress formed the official Continental army, and the next day, appointed George Washington commander-and-chief. Washington immediately set out for Boston to take control of the situation. He set up his head quarters in Cambridge and promptly began teaching the troops how to be an army.

The first thing he did was divide the army into three sections. The right section was stationed at Roxbury and led by Major General Artemas Ward, the middle section was stationed near Cambridge and led by Major General Israel Putnam, and the left guarding the exits from Charlestown, was led by Major General Charles Lee.

After the battle at Bunker Hill, where the Americans lost Charlestown, there was no more fighting between the two armies throughout the summer, aside from some small skirmishes.

Battle of Bunker Hill, depicted in 1909 by E. Percy Moran

Public domain image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Americans worked hard at reinforcing their army and its three sections. This made their defenses very strong. They also stationed sharpshooters on the hill tops to harass the British lines as they went about their patrol.

Finally, the British broke the silence. On July 30, 1775, they raided Roxbury. While the American wing stationed there defended, another wing headed to attack the lighthouse on Lighthouse Island. They successfully destroyed it, cutting off the ability for the British to communicate with their ships at night.

During September, General George Washington learned that the British did not plan to attack until they were reinforced. This was good news for him. He then sent 1,100 men, led by Benedict Arnold to attack Canada.

Washington feared that the winter months would break up his army, due to illness from the cold. He wanted to plan an invasion of the city, but his men convinced him to postpone the attack for a few more weeks. During these weeks, he had his men raid near by cities, towns, and shops: anywhere they could find to get sustenance.

In November, a colonel under Washington, by the name of Henry Knox, came up with a plan to move the guns from Ticonderoga into Boston. Washington was pleased with the plan. He was, in fact, so pleased that he promoted Knox to the rank of colonel general. Soon Knox had gone to carry out this task.

In December, everything that had been worrying Washington became a reality. He began to lose many men due to desertion, expired contracts, sickness and in many cases death. He began to see the light at the end of the tunnel, however, upon the return of Henry Knox who brought with him 69 guns and ammunition for the troops.

George Washington, painted by Gilbert Stuart. Washington was commander-in-chief of the Continental Army during the Siege of Boston.

Public domain image, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, in Boston, the British were being reinforced by 11,000 men. Even so, they were running very low on ammunition.

When March of 1776 came, Washington had devised a plan. On the second day of the month, he and a group of soldiers attacked the front of the British forces as a diversion, while another group of soldiers climbed to Dorchester Heights to attack the ships in the harbor.

They gained Dorchester Heights during the night, so they were not seen. However, the British spotted them camped on top of the hill in the morning, and planned to attack. That night there was a fierce snowstorm, preventing this attack.

General Howe, who was in charge of the British troops, considered carrying on with the assault anyway, but then decided to retreat when he considered what had happened on Bunker Hill.

It was then that the British realized they could not defend themselves from the surrounding American forces, and sent a messenger to Washington. They proposed that they would leave Boston without destroying anything as long as the Americans would not attack them on their way out. Washington agreed to this and, after having waged an 11 month siege, took back Boston. The British sailed away, and the Americans kept hold of Boston for the rest of the war.